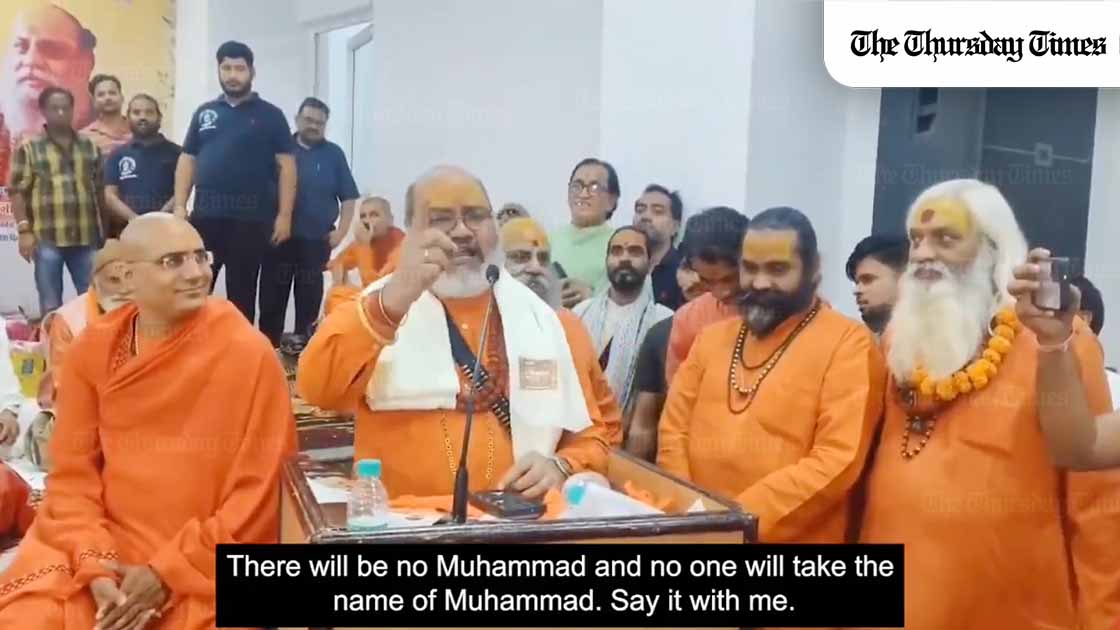

Yati Narsinghanand Saraswati’s latest speech is not a spontaneous outburst but a precise articulation of a political theology that treats the eradication of Islam as sacred duty. In the viral clip, delivered after Zohran Mamdani’s election as New York City’s first Muslim mayor, he calls Islam a “cancer,” vows that “Islam will not remain, only Sanatan will remain,” and goes so far as to promise that neither the Prophet Muhammad nor those invoking his name will survive. This is eliminationist language, framed as devotion, performed before an approving audience, and broadcast into an already polarised ecosystem. It demands to be read not as noise but as evidence.

After London’s mayor Sadiq Khan, New York’s mayor Zohran Mamdani is now also a Muslim of Indian origin. This means we are living in an age of great destruction. I assure you all that we will wipe out this cancer from the face of the earth. Islam will not survive, only Sanatan… pic.twitter.com/q0Iuq4k0xj

— The Thursday Times (@thursday_times) November 9, 2025

Narsinghanand is by now a central figure in India’s organised hate architecture. Head priest of the Dasna Devi temple in Ghaziabad, with a documented record of inflammatory speeches and multiple FIRs invoking sections 153A, 295A and 505 of the Indian Penal Code, he rose to national prominence around the Dasna temple incident and through a steady stream of anti-Muslim invective. Reports show at least six cases related to promoting enmity and hate speech, including for disparaging remarks about the Prophet at the Press Club of India. Most notably, he was a key organiser of the Haridwar Dharam Sansad in December 2021, where open calls for the mass killing of Muslims were issued from a religious stage. He operates, in other words, as a repeat and intentional actor, not an uninformed or isolated sadhu.

The content of the present speech follows the same arc but with greater clarity. The framing is apocalyptic: “this is an era of destruction,” proof that the world is in moral collapse. The solution he offers is not democratic contestation or ideological debate but the physical and symbolic removal of Islam from the earth. The chant “Har Har Mahadev” is deployed not as a generic devotional slogan but as a binding oath to a political project. His references to not being a “born sadhu” and to having an “original profession” known to his guru are deliberate hints at militancy and disciplined obedience. This is the vocabulary of a cadre, not of a contemplative monk.

His invocation of Zohran Mamdani is strategically chosen. Mamdani’s election in 2025 as New York City’s first Muslim and South Asian mayor on an explicitly progressive platform has already attracted Islamophobic backlash in the United States, including attempts to frame him as disloyal or dangerous. Narsinghanand distorts Mamdani’s biography into a story of an “Indian Muslim” with Hindu familial ties, then holds this up as proof that “destruction” has arrived. The message to his audience is simple and poisonous: Muslim political success anywhere, even via democratic process, is part of an advancing civilisational enemy. A municipal election in New York is thus recoded as a trigger for Hindu mobilisation in India. It plugs local Hindutva grievance into a global Islamophobia circuit.

When he invokes “London” before turning to New York, he is not being vague; he is reaching for Sadiq Khan and Zohran Mamdani as twin exhibits in a story he tells his followers about Muslim capture of Western power centres. Both men are democratically elected mayors of global cities; in Narsinghanand’s cosmology they become proof of civilisational decay, milestones in an imagined march of Islam that must be reversed. By pairing London and New York in one breath, he recodes routine electoral outcomes into a transnational siege narrative, inviting his Indian audience to see every Muslim political success, anywhere, as a personalized affront requiring a Hindu response.

Measured against India’s own criminal law, this speech sits comfortably inside the zone of punishable hate advocacy. Section 153A IPC penalises promotion of enmity or hatred between groups on grounds of religion. By characterising Islam as a “cancer” and declaring that neither the Prophet nor his followers should remain, Narsinghanand directly targets a defined religious community in language whose natural consequence is hatred and hostility. In a climate of recurrent communal tension, it is more than reasonably foreseeable that such words are “prejudicial to the maintenance of harmony,” which is the statutory standard. The ingredients of 153A are met without interpretive gymnastics.

Section 295A IPC, which addresses deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings, is even more clearly engaged. Narsinghanand has an established history of derogatory statements about the Prophet for which FIRs have already been registered. When he now publicly pledges to wipe out both Islam and the very name of Muhammad, in an atmosphere charged by past incidents, malice and deliberation are not in doubt. This is not theological critique but targeted humiliation and erasure of core objects of Muslim veneration. Coupled with Section 505(2), which criminalises statements promoting enmity or ill will between religious groups, and its aggravated forms for speeches made to assemblies, the statutory framework captures precisely this kind of performance.

The new Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita provisions that replace parts of the IPC preserve these core offences in substance, and India’s higher judiciary has repeatedly affirmed that secularism and equality are part of the Constitution’s basic structure. In theory, there is no legal vacuum. The question raised by this clip is not whether India has the tools to respond, but whether those tools are being applied consistently, or are selectively deployed against protesters, minorities and journalists while ideologues like Narsinghanand operate with near impunity.

Under international human rights law, the obligations are equally unambiguous. Article 20(2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which India is a party, requires states to prohibit “any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence.” The Rabat Plan of Action refines this through a six-part threshold test, focusing on context, status of the speaker, intent, content, extent and likelihood. Applied to Narsinghanand, each element is aggravated, not mitigated: he speaks as a religious authority in a charged communal environment, uses eliminationist language about a protected group, addresses a mobilised audience in person and online, has a documented pattern of similar speech, and operates in a setting where anti-Muslim vigilantism and discrimination are neither theoretical nor rare. On Rabat’s own conservative criteria, this is advocacy that states are obliged to curb.

There is also a serious argument that parts of his discourse edge toward direct and public incitement to genocide. The Genocide Convention protects religious groups; calls for their destruction, “in whole or in part,” combined with intent, can amount to incitement even absent immediate mass violence. Narsinghanand has previously called for war against Islam, for seizing the Kaaba, and presided over forums in Haridwar where speakers urged Hindus to take up arms and kill Muslims. When he now pledges that no one who bears the Prophet’s name should remain, that rhetoric is no longer separable from a corpus of explicit exterminatory fantasy. Whether a court would meet the precise legal threshold is a technical question, but from an atrocity-prevention perspective, this is classic pre-genocidal propaganda.

Crucially, his words do not exist in a vacuum. At Dasna Devi temple, a teenage Muslim boy was assaulted for drinking water and banners were erected warning that Muslims were not allowed inside, an exclusionary regime publicly associated with Narsinghanand’s line. The Haridwar Dharam Sansad generated national and international alarm; yet accountability was hesitant and partial, with key figures either briefly detained on unrelated charges or left in legal limbo. Article 14 and other investigators have documented a series of similar events across states, revealing not isolated incidents but an organised circuit of hate assembly. The pattern is simple: maximalist speech, minimal consequence.

This gap between law on paper and law in practice produces what can be called outsourced extremism. The formal state does not officially endorse genocide or expulsion. It cultivates instead a penumbra of religious figures, television hosts and local leaders who speak a cruder language that core political actors can publicly disown while privately benefiting from its mobilisation power. Selective policing, administrative indulgence and performative or delayed FIRs signal to supporters that these hate entrepreneurs are effectively protected, while critics and minorities face a very different standard. The outcome is an ecosystem in which speeches like Narsinghanand’s are both visible and viable.

Narsinghanand’s latest intervention has to be read inside Modi’s India, where the symbolic centre of gravity has shifted sharply. From the state-choreographed consecration of the Ram Mandir, to the normalisation of bulldozer punishment in Muslim localities, to campaigns against “love jihad” and public namaz, institutional behaviour has repeatedly echoed or rewarded core Hindutva talking points. None of these acts, taken alone, mandates genocide, but together they recode Muslims as a problem population and embolden the fantasy that India is, in essence, a Hindu state with conditional space for others. In such a setting, when a prominent priest promises the end of Islam, it sounds less like fringe delusion and more like the logical terminus of a mainstream narrative stripped of its remaining restraints.

This is why the speech matters beyond its immediate offensiveness. It is a stress test of the Indian constitutional order and of international commitments that India voluntarily undertook. To tolerate explicit vows of religious eradication from a figure of this profile is to normalise the language that historically precedes mass atrocity. Robust enforcement of existing criminal law, clear political repudiation by those in power, and institutional signals that such advocacy is incompatible with Indian secularism are not favours to Muslims or to liberals. They are the minimum conditions for preserving a multi-religious republic from those who openly announce their intention to unmake it.