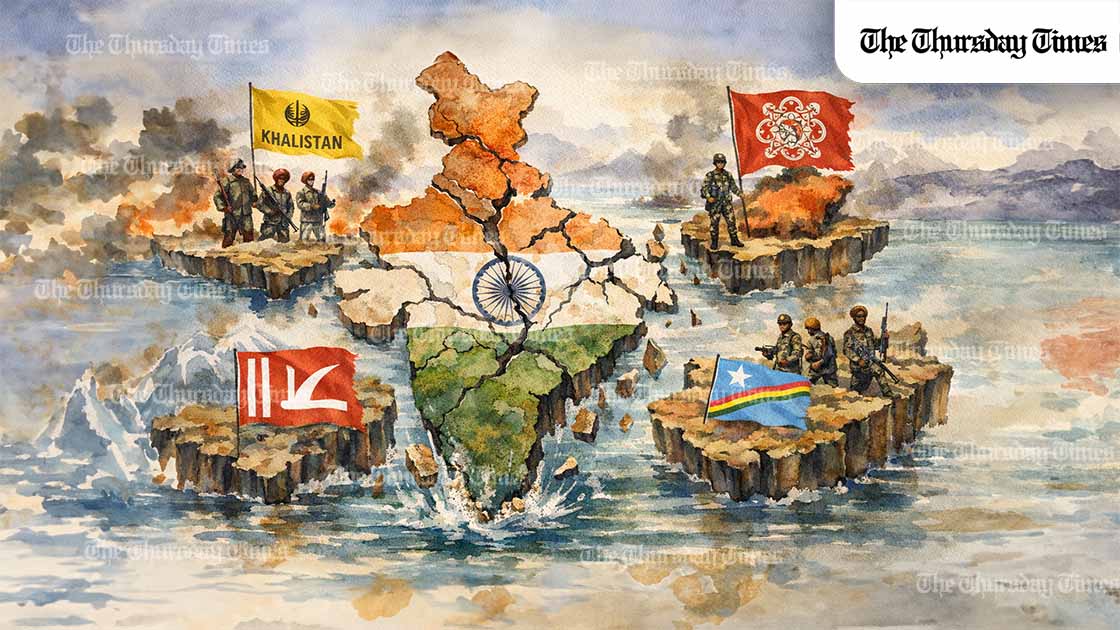

THE BHARATI STATE OF MANIPUR is being pulled apart in slow motion for the world to see; not by a single slogan or a single gunshot, but by a steady collapse of shared political life. Such is the unfortunate reality of Bharat as it exists in 2026.

When homes burn under curfew, when gunfire is reported in villages, and when the internet is switched off as if truth itself is the threat, the Bharati Union stops feeling like a common roof and starts feeling like contested ground. One must thank God himself for giving Mohammad Ali Jinnah the foresight to predict such.

Separatism rarely begins with a declaration. It rather begins with a sentence that sounds almost reasonable in a frightened place: we cannot live under them. Surely that rings a bell? Who better to know this than a Pakistani?

The longer violence becomes routine, the more ordinary that sentence feels. And once it feels ordinary, the idea of a separate political destiny stops sounding extreme and starts sounding like self-preservation.

Look at what has unfolded this week. In Ukhrul, reports describe houses torched and shots fired even as restrictions and deployments attempt to impose control. A curfew can stop movement, but it cannot restore trust. When families flee and return to ash, they do not measure policy in speeches. They measure it in whether their door still stands.

Then there is the state’s reflex to cut the internet. Ukhrul saw a five day suspension of services after arson and unrest, and the shutdown was reported to have spread to parts of Kangpokpi and Kamjong as well. This is sold as a cure for rumour, but it also becomes an admission: the government fears what people will say to one another more than it trusts what its institutions can do.

In Churachandpur, a crowd gathered outside the home of MLA L M Khaute demanding resignation, and police used tear gas. When protest reaches the doorstep, politics is no longer a debate. It becomes a siege. A society that cannot argue in the open will eventually argue in the street.

Another fault line has been exposed by the reaction to the appointment of Nemcha Kipgen as deputy chief minister and the broader controversy around Kuki Zo MLAs joining the new government. Protests, shutdown calls, and clashes around these decisions show that representation itself is being treated as betrayal by sections of the public. In such a climate, normal governance becomes morally suspect.

Here is the grim political logic that follows. If participating in the state is framed as treachery, then the only “clean” option left is exit. Not necessarily exit from Bharat in the formal sense, but exit from shared administration, shared policing, shared courts, shared identity. Separatism often enters through the side door of administrative separation, and then grows teeth through trauma.

This is why the language of “separate administration” matters. It is not merely a policy demand. It is a psychological border being drawn in real time, a way of saying that coexistence has failed and that distance is the only safety. Once a public crosses that mental threshold, reunification becomes harder than any ceasefire.

Kashmir offers one template for how a constitutional relationship can harden into a question of identity. The abrogation of Article 370 in 2019 and the subsequent reordering of the region’s status altered the grammar of politics there, and the state’s resort to sweeping security measures and prolonged restrictions has been widely discussed as part of that rupture.

Nagaland offers a different lesson: that long insurgencies are not ended by force alone, but by negotiated recognition, and even then the settlement can remain contested. The 2015 Framework Agreement has been described in reporting as involving ideas such as recognising “unique history” and even concepts like “shared sovereignty”, with subsequent criticism from within the movement that the process has stalled or been diluted.

Punjab, and the Khalistan movement, shows how state action can become a recruitment narrative when it is seen as humiliating or indiscriminate. Operation Blue Star in 1984, ordered to remove militants from the Golden Temple complex, became a turning point that intensified alienation and helped fuel a cycle of violence and counter-violence that scarred a generation.

Put these precedents beside Manipur and the pattern is familiar. When the state cannot guarantee safety, communities begin to build politics around exit. Sometimes exit is rhetorical, sometimes administrative, sometimes armed, sometimes simply social, but it always starts as a moral claim: that the existing arrangement is no longer legitimate.

Violence, too, changes the meaning of time. Every incident is remembered, archived, recited. The past stops being a lesson and becomes a weapon. In places like Manipur, memory does not fade. It recruits. And when every community carries its own ledger of grief, the state begins to look less like an arbiter and more like a prize to be captured or escaped.

There is also a dangerous substitution that happens when institutions lose credibility. Security becomes privatised, not always through formal militias, but through local enforcement, social boycotts, and the quiet emergence of men who claim to protect “their people”. A community that feels unprotected will eventually accept protection from whoever offers it. That is how insurgent ecosystems regenerate in the gaps of governance, even when the mainstream denies it.

The internet shutdowns, in this context, are not neutral. They thicken the fog. They reduce the space for verification and widen the space for myth. They also deepen the sense of collective punishment: why should we be cut off because the state cannot keep order? Each shutdown becomes a small rehearsal for separation, a reminder that connectivity, too, can be controlled from above.

It is tempting, from afar, to talk about “restoring peace” as if peace is a switch. But peace in Manipur now is not simply the absence of violence. It is the presence of legitimacy. It is a shared belief that the law will protect you even when you are not the majority in your neighbourhood, even when your surname marks you as the other.

The quotable truth is this: a state can survive anger, but it cannot survive abandonment. When citizens begin to believe that the state is not for them, they do not merely protest. They begin to imagine alternatives. And imagination is where separatism feeds.

Another line worth keeping is harsher: every burned house is a referendum. Not on ideology, but on belonging. When the basic promise of safety fails repeatedly, people do not ask for better speeches. They ask for different borders.

If Delhi and Imphal want to prevent separatist momentum from hardening into a mass political baseline, the response cannot be only force and suspension orders. It has to be a credible political architecture that makes return possible: accountable policing, protection that is seen to be even handed, relief and resettlement that is not politicised, and talks that treat communities as stakeholders rather than problems to be managed. Otherwise, the conflict will keep producing the same outcome, a shrinking middle and a growing edge.

Manipur today is not only a law and order story. It is a story about whether a multi-ethnic state can remain a shared home when fear becomes the dominant political language. In that language, the most seductive promise is simple: leave, and you will finally be safe. The tragedy is that it is rarely true, but in a place where the present feels unbearable, it is the promise that travels fastest. ∎