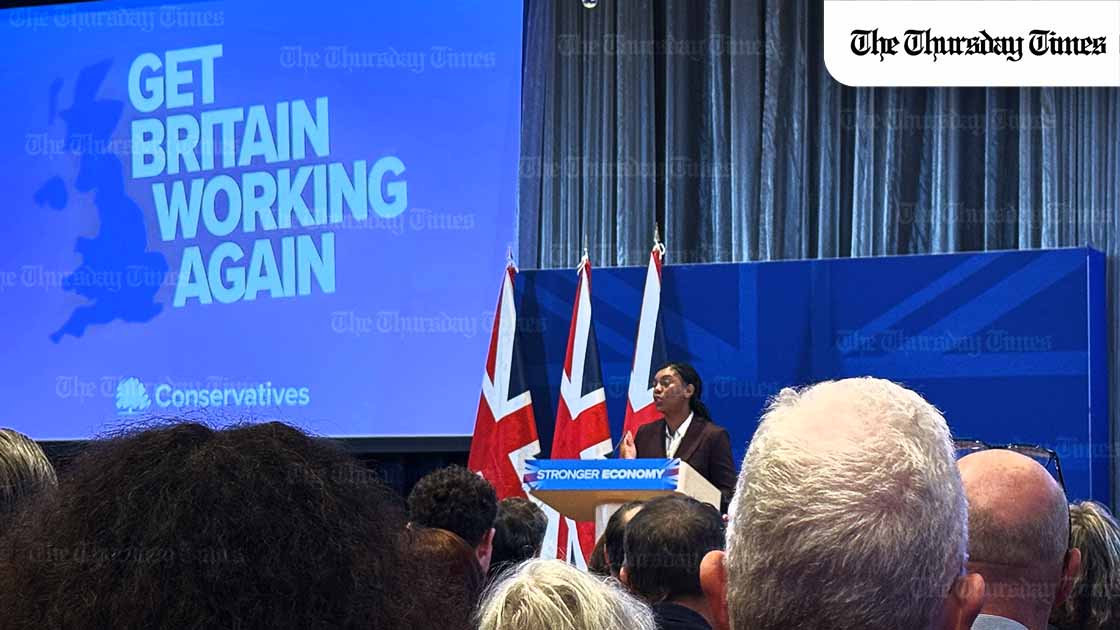

CENTRAL LONDON (The Thursday Times) — Kemi Badenoch’s speech at Glaziers Hall today was billed as a welfare address, but it landed more like a manifesto in miniature. Framed as a call to “get Britain working again,” she set out a sharply drawn contrast between her vision of an “opportunity state” and what she described as Labour’s drift toward a “welfare state.” The message was unmistakable: the country must choose between tightening the system or paying indefinitely for its expansion.

Standing before an audience of journalists and policy insiders, she argued that the UK is stuck in a cycle where too many households are better off not working. The examples she deployed — anxiety exemptions, ADHD diagnoses, online “sickfluencers” coaching people through benefits assessments — were chosen to provoke, and they did. Whether or not these cases represent the broader system, they allowed her to set the narrative: welfare has expanded beyond its original purpose, and she intends to reverse it.

One of the sharpest parts of the speech was her attack on relative child-poverty metrics. Badenoch dismissed the widely accepted 60%-of-median-income measure as “not a measure of poverty at all,” arguing that it distorts the picture in both boom and bust. She framed Labour’s policy — lifting the two-child cap and expanding benefits — as a numbers trick that pours money into the system without addressing underlying causes. Her alternative was direct: the best anti-poverty measure is work, and well-paid work at that.

But the headline that will travel furthest is her pledge to conduct a full review of which mental and physical conditions count as disabilities for benefit purposes. Badenoch said the system was “never designed for the age of diagnosis we now live in,” hinting that eligibility standards would tighten. The implication is profound: millions of assessments, exemptions, and long-term claims could be reconsidered under a different definition of disability.

This is where she ventured onto politically treacherous ground. By using conditions like anxiety as examples of “gaming” the system, she risked alienating mental-health advocates who argue that worklessness often stems from genuine conditions compounded by NHS backlogs and economic insecurity. Such critics say the government should fix structural barriers before questioning claimants’ legitimacy; Badenoch argued the opposite, insisting that too much unquestioned eligibility is itself damaging the system.

She further claimed that the household benefit cap “acts more like a sieve than a cap,” with medical exemptions allowing families to bypass it entirely. In promising a review of “every circumstance where benefits pay more than work,” she signalled that the Conservatives are moving toward a fundamental redesign rather than tweaks at the margins. Alongside this came a firmer hint of the party’s fiscal objective: reducing welfare spending back to pre-pandemic levels.

The Q&A revealed another striking moment: Badenoch openly acknowledged that Brexit harmed the UK economy — a rare admission for a senior Conservative — though she framed it as a lesson learned rather than a repudiation. Linking this to welfare, she suggested that Britain now needs to prioritise productivity, growth, and workforce participation to repair long-term economic damage. Welfare reform, in her view, is central to that recovery.

Labour responded within minutes, accusing Badenoch of “delusion” for claiming the Conservatives alone can fix a system they themselves inflated by billions. They argued that her speech amounted to austerity by another name, and that scrapping the two-child cap and raising support is necessary to stop rising child poverty. To Labour, today’s message was clear: she intends to cut where they intend to support.

The political dividing lines could not be clearer. Badenoch casts welfare expansion as a moral and fiscal threat; Labour casts her reform agenda as an attack on vulnerable families. Disability groups warn that redefining eligibility risks erasing legitimate needs; her supporters argue that unchecked growth in long-term sickness benefits is economically unsustainable.

Badenoch’s rhetoric today builds on the themes she has voiced for months — that Britain is becoming “a welfare state with an economy attached,” and that too many people are being encouraged, medically or culturally, to opt out of the workforce. What was different this time was the level of detail and the scope of the promised review. Her argument is no longer just philosophical; it now has direct policy targets.

Whether this agenda wins public support will depend on how the debate evolves. Many voters agree with the instinct that the system should be fair, not easily exploited, and more closely tied to work. But the risk — politically and socially — is that sweeping changes to mental-health and disability criteria ignite backlash from communities who feel unseen or misrepresented.

In the end, Badenoch’s speech was less about today’s welfare system and more about Britain’s future economic identity. Is the country prepared to tighten benefits in pursuit of higher employment, or will it prioritise reducing poverty even at the cost of higher public spending? She placed that question squarely before the electorate. It will not be resolved quietly.