LAHORE, IN LATE DECEMBER, CARRIES a particular sort of light: the winter sun thinning into gold, streetlamps warming the edges of bougainvillea, and the city holding its breath the way it does before a wedding.

Exactly a decade ago, at Jati Umra that evening, the Sharif estate was already dressed for celebration, festooned and humming with the busy tenderness of family preparations, the kind where cousins drift in and out with trays, where elders supervise with quiet authority, where the air smells faintly of jasmine, ghee, and excitement. Then the rotors arrived and the sound cut clean through the softness, a private helicopter settling into the grounds as if it belonged there, as if borders were not barbed facts but negotiable habits.

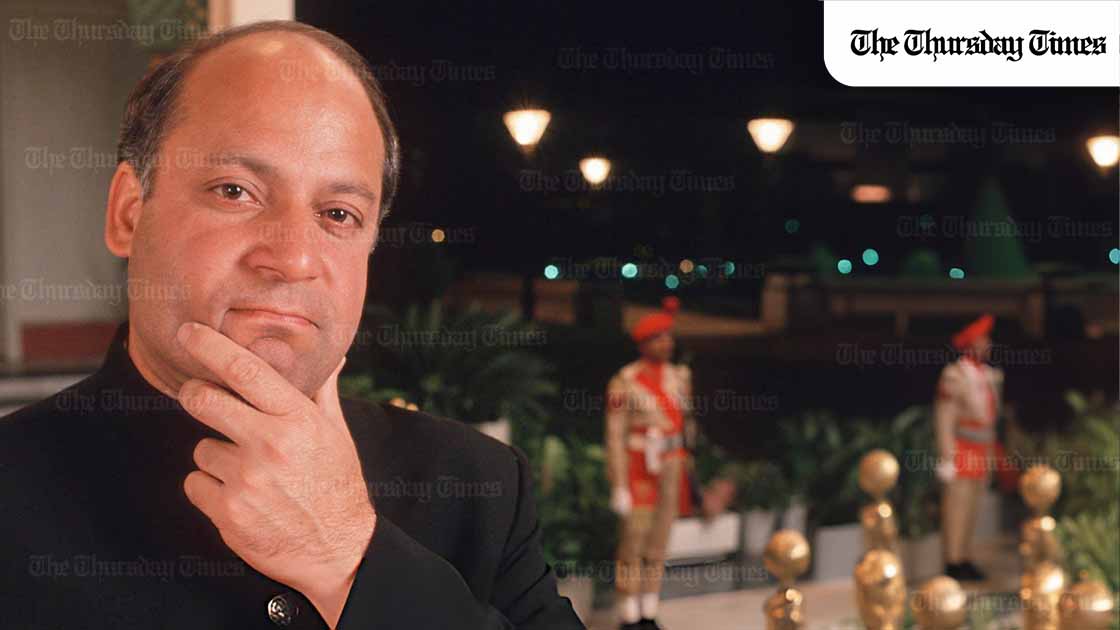

Two men met, hugged, smiled in a way that did not look rehearsed, and walked toward the house as though history were not a barricade but an old treadmill you could step off if you chose. Photographs travelled fast, as did the astonishment. Reuters, reporting the moment that still feels cinematic ten years later, called it a “surprise” stopover: Narendra Modi returning from Kabul, landing in Lahore to meet Nawaz Sharif on Sharif’s 66th birthday, after a phone call earlier in the day in which Modi asked if he could come and Sharif replied like a host, not a rival: please come, have tea with me, at the very least.

The exchange worked precisely because it was almost too human for geopolitics. In South Asia we are trained to expect choreography, to expect statements written like legal documents, to expect leaders to meet as though they are entering a courtroom. But here was something softer and therefore rarer: a landing, a welcome, an unguarded moment of warmth. It made the region feel, for an hour or two, like a place capable of intimacy again. It also revealed something essential about Nawaz Sharif’s political temperament, the part of him that is easiest to mock and hardest to replicate: he believed in contact the way serious men believe in deterrence. Not as sentiment. As strategy. Not as poetry alone. As policy. Lahore in 2015 was not magic. It was method. It was the continuation of a long argument he had been making with the state, with the street, and with history itself: that engagement is not surrender, that talking is not treason, that a leader’s duty is not to inherit hostility but to manage it, dilute it, and eventually outgrow it.

If one wishes to understand Nawaz Sharif’s legacy in its clearest shape, you must begin earlier, in February 1999, when he persuaded Atal Bihari Vajpayee to come to Lahore. Another prime minister from the BJP, another moment when the world looked up and asked, almost in disbelief, is this possible here? Vajpayee arrived on the inaugural bus service, a gesture whose brilliance lay in its simplicity. No spectacle of military might, no grandstanding, just wheels on a road that had always existed, carrying the message that geography is not your enemy unless you insist on making it one. Out of that visit came the Lahore Declaration, signed on 21 February 1999, in which both governments affirmed their commitment to peace, stability and mutual progress, recognised the added responsibility that nuclear capability imposes, and emphasised confidence-building measures designed to reduce the risks of misunderstanding and accidental escalation.

It is fashionable to recall Lahore 1999 as an interrupted dream, to jump quickly to what followed and treat the attempt as futile. But that reading misses the point of statesmanship. The point was not that one summit would dissolve decades of dispute. The point was that Nawaz attempted to change the default setting, to make dialogue normal enough that it could survive the next crisis, the next election, the next wave of public anger. He kept trying to build a region where leaders could talk without first proving their toughness, where the act of meeting did not require a scandal to justify it.

That is why the Lahore stopover of 2015, a lifetime later, felt like an echo of an older instinct rather than a random deviation. Sharif was still trying to stitch the region into something wearable, something ordinary. He was, in his most serious moments, a believer in the unglamorous architecture of peace: the paperwork, the protocols, the trade corridors, the visas that do not turn cousins into foreigners, the transport links that treat ordinary people as citizens rather than security risks by default.

Peace is not only a handshake. Peace is systems that make handshakes unnecessary because cooperation becomes routine. Sharif wanted the boring peace, the kind that hides in timetables and customs forms and student exchanges and business delegations. He wanted people-to-people contact not as a slogan but as a policy lever, because once societies begin to meet, trade, marry, study, and invest, hostility becomes harder to sell. It is no accident that when diplomats spoke after Modi’s 2015 visit, the language returned to strengthening ties and facilitating people-to-people contact.

What made Sharif distinct, and what your politics will not let you say without inviting a fight, is that his imagination for connection did not stop at the Wagah border. It extended inward. He also wanted Pakistan to be tied together again, stitched into a nation spacious enough to hold its minorities with dignity, not as tolerated guests, not as decorative mentions on national days, but as citizens whose belonging could not be negotiated away. This is where his legacy is at once more intimate and more courageous, because in Pakistan the cost of saying “we” too widely can be immediate. When Sharif chose to put minorities front and centre, he did not do it in the safest language. He did it with ownership.

In November 2015, at a Diwali ceremony, he spoke directly to the Hindu community in terms that sounded less like a politician addressing an audience and more like a leader insisting on the shape of the republic. The Express Tribune quoted him saying, “Every community living here whether Hindu, Muslim or Parsi, belongs to me and I belong to them. I am the prime minister of all communities.” Dawn reported on the same occasion that he vowed to protect the rights of all religious communities, and noted the significance that organisers attached to his presence, describing him as the first prime minister to join the Hindu community in celebration of Diwali.

These were not empty lines in a country where public life often teaches minorities to shrink themselves for safety. When a prime minister stands in that space and speaks like that, he is not merely greeting a festival. He is attempting to rewrite the emotional constitution, to make it harder for the nation to imagine itself as a single note. He is, in a sense, arguing that Pakistan can be a bouquet, not a blade.

He backed symbolism with requisite law. In March 2017, the Prime Minister’s Office announced that on the advice of Prime Minister Muhammad Nawaz Sharif, the President assented to the Hindu Marriage Bill, a landmark that provided legal recognition and structure to Hindu marriages, protecting families whose personal status had too often been left to informal arrangements and bureaucratic uncertainty. It is easy to underestimate how deeply “paper” matters to minorities. A legal framework is not glamour, but it is dignity; it is the difference between a marriage that exists only socially and a marriage that the state recognises when questions of inheritance, divorce, custody, and identity arise. It is policy as belonging. It is what inclusion looks like when it stops being a speech and becomes a statute.

With Christians, too, he sought the language of shared citizenship, not outsider tolerance. The Prime Minister’s Office published a Christmas message that begins plainly: “On the joyous day of Christmas, I wish merry Christmas to our Christian brethren in Pakistan and all over the world.” This might sound routine in other countries. In ours, official language is never neutral; it teaches the public who counts. Calling Christians “brethren” is not simply courtesy. It is a deliberate placement of Christians inside the national family.

Then there is the community that Pakistani politicians often treat as untouchable in daylight: Ahmadis. Here, even acknowledging citizenship without euphemism can provoke rage. After the 2010 Lahore attacks on Ahmadi places of worship, Dawn reported that Nawaz Sharif upset religious and political circles by speaking of Ahmadi rights and saying that “Ahmadi brothers and sisters are an asset” of the country, while also stating that Ahmadis were citizens of Pakistan. The Express Tribune reported clerical anger and pressure on him to retract, including statements that revealed, in their cruelty, how contested basic empathy can be. The record shows that he lived under real threat from militant violence, including reporting in 2018 citing intelligence warnings that the TTP might target Nawaz Sharif and his family members.

In Pakistan, this is the shadow that follows anyone who attempts to widen the idea of citizenship. You do not even have to be perfect. You only have to be visible.

Put these strands together and the shape of the man becomes clearer. He was not merely “pro-dialogue” with India as a posture, and he was not merely “pro-minority” as a checkbox. His deeper instinct was integration. He wanted Pakistan to be stable enough to hold its diversity without fear, and he wanted South Asia to be sensible enough to stop treating dialogue like a scandal. He wanted ties that were not episodic, not dependent on moods, but built into the normal functioning of the region. He wanted, in the most literal sense, movement. Movement of people, of commerce, of ideas. Movement that makes dehumanisation harder. Movement that makes war less marketable.

This is why that old line still clings to him, the dream of a subcontinent that can be traversed like a neighbourhood: breakfast in Kabul, lunch in Lahore, dinner in Delhi. It sounds like romance, and it is, but it is also a thesis about geography. It suggests that our map does not have to be a menu of enemies, that the region can be tied together again through the ordinary rituals of life, eating and travelling and visiting and returning. It is not a call to erase nations. It is a call to soften the cruelty with which nations sometimes perform themselves. It is an argument for a future where the border exists, but it does not dominate the imagination.

So yes, ten years on, you can say it plainly. Nawaz Sharif had the guts to engage India, not once, but across his political life. He persuaded Vajpayee to come to Lahore and sign a declaration that tried to bring nuclear responsibility and structured dialogue into the relationship. He hosted Modi in Lahore too, in a stopover the world called “surprise” but that made perfect sense inside Sharif’s long pursuit of normalcy, because he had always believed that a phone call can sometimes do what months of rhetoric cannot. He tried, at every stage, to keep open the idea that neighbours can be more than rivals.

And he tried, with similar insistence, to keep open the idea that Pakistanis can be more than a single story. Hindus, Christians, Ahmadis. He brought them into the national conversation when it was safer to offer them silence. He spoke of them as belonging when others insisted they remain footnotes. He pushed symbolism into law, sentiment into statute, speeches into policies that, however incomplete, still moved the needle of recognition.

That is what makes him a statesman in the truest sense. A statesman is not someone who never fails. A statesman is someone who insists on attempting what the era discourages, someone who spends political capital on the future rather than hoarding it for applause, someone who imagines a region tied together like brothers and then tries, again and again, to make the imagination administrative. His legacy is not a single hug on a Lahore lawn, although that hug will endure. His legacy is the audacity of believing that South Asia can share a table again, and the courage of acting like that belief was not a poem, but a plan.

Happy 76th birthday to the architect of modern Pakistan. May you live to see another 76.